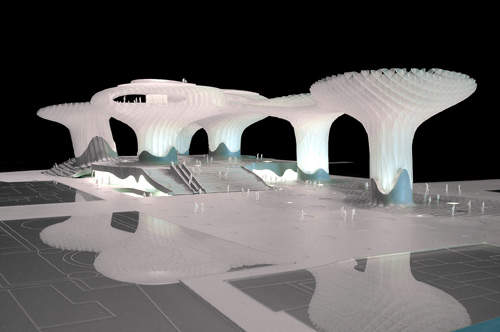

Rising up out of the ground like giant metallic mushrooms, the organic curves and ballooning forms of these ‘parasols’ contrast with the more mundane rectangles surrounding this former parking lot in Seville.

Visualised as a thriving commercial centre where contemporary urban commerce and tourism sit side-by-side with the town’s ancient archaeological remains, the new development, Seville Parasol, is intended to revitalise an uninspiring area of the city.

A large covered market inhabited the square, the Plaza de la Encarnacion, in 1842 before the stalls were knocked down in 1973 and replaced with a car park. An underground car park was planned for the space, until a 1990s archaeological dig revealed the remains of a Roman colony, with figurative mosaics and architecture.

In a bid to integrate the site with everyday commerce, the Sevilla Urban Planning Agency held an international ideas competition in 2004.

The competition was won by J Mayer H Architects, a Berlin-based firm specialising in projects that integrate architecture, communication and new technologies, with the support of global design company Arup, in Berlin. The team was made up of Sebastian Finckh, Wilko Hoffmann, Klaus Kuppers, Julia Neitzel, Dominik Schwarzer, Ingmar Schmidt, Georg Schmidthals, Jan-Christoph Stockebrand and Daria Trovato.

The jury called it ‘an aesthetically pleasing response to the frequently criticised loss of public space’.

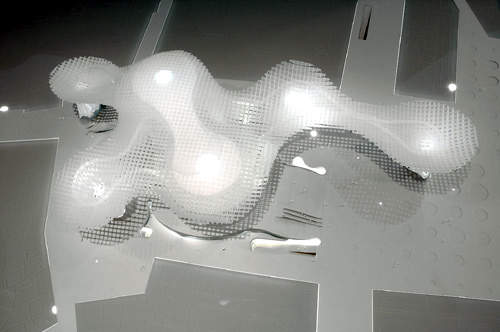

Initial parasol design

Between 2004 and its ‘realisation’ in 2007, when the designs were completed, the roof structure was altered several times in consultation with the structural engineer. A café-restaurant was added after the competition and the floor-plan and accessibility concepts were slightly reorganised.

The various designs of the first and second phases in February and July 2004 were shown to the public. Local vendors and farmers were involved in designing the market stands they are going to rent.

The liquid-like curves of the design are very much in the tradition of avant-garde artists, from Gaudi’s Parc Guell in Barcelona to architect Santiago Calatrava’s Planetarium in Valencia.

The general feel of the designs were inspired by the city of Seville itself, with vaulted church interiors, Moorish ornaments, such as Andalusian grilles, and large sprawling trees. When viewed from different angles, the Parasol structures have a non-repetitive geometric pattern. The sculpture-like shapes were made possible using computerised design and construction methods.

Parasol construction

The general contractor for the project was Sacyr, based in Spain and Ayuntamiento de Sevilla. Half of the project was funded by the city of Seville, and the other half by a construction firm for the timber elements, Finnforest-Merk (FFM) from Aichach, in Germany.

The firm will have the right to use the building as a concessionaire for 40 years, with rent from the marketstands, bars, cafés, restaurant and special events, while being responsible for the maintenance of the building. After that, the building will be back in the hands of the city of Seville.

The structure was officially inaugurated in March 2011. By late 2007, the foundations of the structure was already laid, and all the underground elements were established, with the stairs and the ramps cast. Two concrete trunks with elevators were erected, and the platform was in place. The next step was the wood, which is separate from the underground construction and the construction at zero level.

Although the interlinked mushrooms in the final concept seem like an amorphous blob, they are actually designed on four levels. The museum connected with the Roman excavation is in the basement with an entrance in the thickest parasol column, and a large stairway leading up to street level. The air-conditioned, covered market is on the ground floor at street level, and above this is an elevated plaza with bars and restaurants, where people can watch a concert or sporting events.

On the second floor, approximately level with the eaves of the surrounding buildings, is the panorama deck and the Sky Cafe, with opened sunshades overhead. A futuristic Sky Walks walkway offers views of Seville’s old city, 22m above the ground. Visitors can also catch glimpses of the other platforms down to the museum through holes in the platforms, and look out over the restaurants from little terraces.

All the layers are accessible via stairwells in the columns and it’s also possible to take a lift 30m to the inner lip at the top of the parasols. The six-parasol structure also houses a farmer’s market, metro station and numerous bars and restaurants underneath and inside the parasol.

Material used for making the Metropol Parasol

The first priority for the architects were the questions of form and space, with materials the second consideration. Individual pre-cast, bent metal pieces were one option, as well as the kind of plastics used in shipbuilding.

Motivated by the successful use of wood in their student dining hall in Karlsruhe, the architects decided on FFM’s Kerto-Q light timber beams with a polyurethane coating, which is cheaper than metal but still durable.

The polyurethane coating protects the wood and allows it to breathe – a sort of natural air conditioning – and the wood itself doesn’t give off hazardous fumes when it burns. It is also sustainably planted, with a certificate PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification schemes), granted by the Finnish Forest Council of Certification.

The free-standing parasols cover an area of 150m x 70m, which is one of the largest architectural timber structures ever built.

Unusually the parasols are a composite structure, with the wood reinforced with steel – or pretensioned – to carry the tension forces.

The main elements are penetrated by two steel rods at the point where those sections meet, and these parts aren’t visible from the outside. Structural engineers Arup conducted research with the polytechnical college in Augsburg, near Munich, to test the wood’s behaviour.

Interior fountains and plants also help to provide a cool climate during the intense summer heat. The coat of the structure is self cleaning, and only needs repainting every 20 to 25 years.