The Fulton Center (formerly Fulton Street Transit Center), one of the busiest interchanges on New York’s subway, was inaugurated on 9 November 2014 and opened to the public the following day. The new transit hub features a re-engineered platform and easy underground access to 12 NYC subway lines and six stations, handling 300,000 passengers a day.

The MTA appointed Arup as the prime design consultant in 2003 to lead a 25-member team that included building design architect Grimshaw Architects, historic preservationist and architect Page Ayres Cowley Architects and HDR Daniel Frankfurt to rationalise the entire complex and rehabilitate the existing stations.

The Fulton Street and Broadway-Nassau stations were originally built separately between 1905 and 1933 when the system was run by competing operators IRT, BMT and IND.

As they competed for users, there was no incentive to enable straightforward transfers from one line to another. Without a comprehensive works programme, operators made additions and alterations on an ad hoc basis.

As a result, the network became a maze of dark, narrow entrances and passageways, resulting in complex transfer routes and crowded platforms. The Fulton Center was formally designated Fulton Center in May 2012.

Fulton Center transport hub

The MTA’s environmental impact statement for the complex identified the need for ‘a less congested and circuitous station that would be accessible to people with disabilities (in accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act), easily recognisable from above ground and directly connected to the World Trade Center (WTC) site.

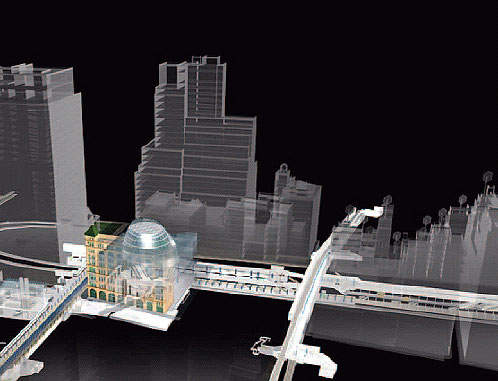

The owner of the Fulton Street / Broadway-Nassau complex, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) began the works to reconnect the hub’s six individual stations in December 2004 to streamline its network and increase capacity from nine to 12 lines.

MTA’s brief called for rationalisation of surface-level access points and an entrance building at the corner of Fulton Street and Broadway, a block away from where the WTC once stood. A pedestrian concourse under Dey Street was constructed that links Fulton Street with the WTC site.

Property acquisition and preservation

Construction required the acquisition of all buildings on the east side of Broadway between John and Fulton Streets, although the nine-storey, federally listed Corbin Building was preserved and incorporated into the complex. An ornate office block designed by Frances Kimball and built in 1889, it sits adjacent to the new subway entrance.

This ornamental brick and terracotta building is decorated with elaborate arches and large arcades, which New York’s Historic Preservation Commission describes as an important part of the city’s historical fabric.

Other properties along Broadway, such as a former Childs restaurant and the 102-year-old Girard Building, were razed.

New York State authorities acquired a two-storey building at 189 Broadway, which was occupied by the World of Golf store, to create a street-level entrance to the Dey Street concourse.

Fulton Street’s Marine Grill Murals, designed by Fred Dana Marsh in 1913 and installed in the station as part of a project sponsored by MTA Arts for Transit and the New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee, were preserved at the site for reinstallation.

Rand design

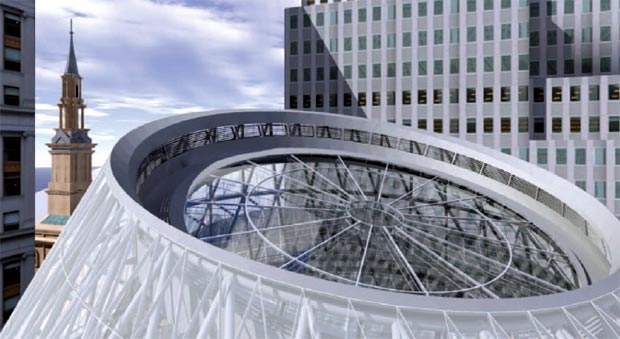

Its main feature is a 110ft-high asymmetrical tapered dome that rises above the underground transit hub. Clad with high-performance translucent glass, this triangulated steel structure supports a filigree metal inner skin, designed in collaboration with artist James Carpenter.

First and foremost, this acts as a beacon to commuters. The 366,000ft² Fulton Street / Broadway-Nassau station complex had 30 entrances, with many difficult to locate among the crooked streets of lower Manhattan.

The senior architect at Grimshaw, Robert Garneau, expected Fulton Street to become a key landmark that would allow people to recognise the station easily.

The Fulton Street Dome

Although a very modern structure, the Fulton Street dome was inspired by a classical icon, the Pantheon in Rome. The former temple features a gap in its dome called an oculus, which allows light into the interior.

Likewise, Grimshaw and Carpenter designed their dome so that it allows natural light into the space below. Their aim was to draw light into the complex’s nether regions, two levels below the street and involved a lot of intricate work.

Carpenter’s dome has a variety of finishes; some are reflective, while others are perforated to let in light. Sunlight animates these surfaces just as it does with the marble in the Pantheon. In fact, the designers want the light to hit a specific point, the edge of the solar reflector, at 12pm on each equinox.

Increased illumination, both natural and artificial, was part of the plan to improve passenger flow around the complex. Likewise, local landmark St Paul’s Chapel is visible from the mezzanine level, a major point of orientation for commuters emerging from the seven subway lines.

Improving passenger flow at Fulton Street, New York

While Grimshaw works on the dome, Arup concentrated on replacing Fulton Street’s network of stairs and ramps. The aim of this project was to reduce platform congestion, improve passenger safety and give better access to people with disabilities.

The engineering firm had to monitor passenger flow closely, but Arup’s project director Dave Palmer said working out how to ease congestion was a fairly straightforward process.

Exits are spaced out to enable people to cross from one platform by cutting across corners.

Connected to the hub is a 350ft underground concourse at Dey Street, between Church Street and Broadway, that provides a link to Santiago Calatrava’s under-construction PATH terminal and 1/9 subway station, which is set to be part of the Freedom Tower complex at the former WTC.

Surrounding the dome, a 50ft-high glazed entrance pavilion maintains the street frontage on Fulton Street and Broadway. This provides retail and restaurant amenities.

Travellers can enter Fulton Street through restored arches in the base of the Corbin Building and pass by the inverted arches that form its foundations, which are exposed to public view.

Working schedule

Arup and its partners worked to a tight schedule that left little room for delays. Construction began in late-2005 as MTA was waiting for compulsory purchase orders to arrive.

Arup, therefore, divided engineering work into a series of discreet packages, beginning with the redevelopment of lines 2 and 3, said Palmer PB-Lend Lease served as the consultant construction manager.

Just as challenging is the fact that the subway runs 24 hours a day. To this end, the firm worked out an arrangement with MTA to identify times when it could close down parts of the network, such as over the weekends.

As part of its downtown renewal plan, the MTA also built a new terminal at South Ferry to enhance service on the 1 and 9 lines and improve the connection to the Staten Island Ferry terminal.