Prefabricated buildings are far from a new concept. In the UK, around 150,000 temporary prefab houses were built after World War II, to house the families bombed out of their homes. The Crystal Palace exhibition hall, built in 1851, was a modular structure completed in less than six months. And after the Romans conquered Britain, they used prefabricated building elements to construct their forts.

Given the abundance of historical examples, it may seem strange to see prefab touted as an innovative idea, with discussions couched in the language of hyper-modernity. And yet the prefab boom is very real, with demand surging across the world.

According to a 2015 report by Global Industry Analysts, global shipments of prefabricated housing are set to reach 1.1m units by 2020, largely thanks to a focus on sustainability and cost reductions. The feeling throughout the industry is that prefab has turned a corner – no longer associated with poor-quality, unsightly buildings, it is being pegged as a solution to some of our most pressing construction needs.

Redressing supply shortages

For Jeff Wilson, CEO of the Texas-based housing startup Kasita, what we are seeing today amounts to the realisation of a long-held architectural goal.

“Since Buckminster Fuller the world has been discussing the ‘modular promise’ in one aspect or another, but the promise was always nothing more than a promise,” he says. “However, we are now entering a ‘post-modularism’ phase of building, due not to new designs or even new materials, but to a convergence of societal, economic, consumer, and nomadic trends.”

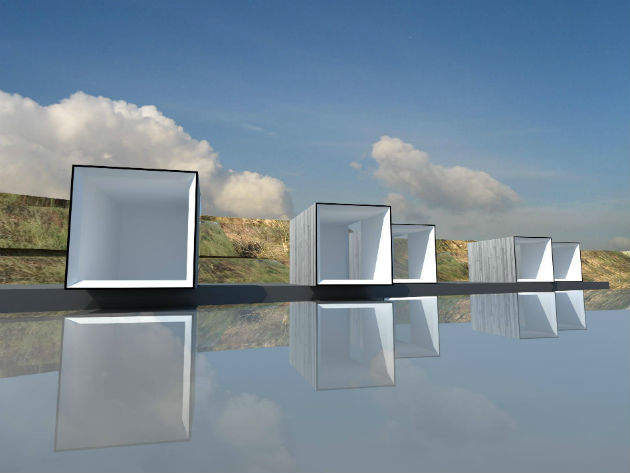

Kasita offers small, prefabricated housing units that can be assembled off-site and delivered in a matter of weeks. At just 352 square feet, they are undoubtedly compact, but promise to offer ‘outsized functionality’: a simple, lightweight, low-footprint home with everything the inhabitant needs.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAccording to Wilson, prefabricated homes of this kind will be imperative if the housing crisis is to be solved. Having spent a year living in a 33 square foot dumpster, to test the limits of habitable space, he is confident there are ways to redress supply shortages without resorting to government subsidies.

“We’re not going to solve the housing crisis with the same sort of thinking and methods that created it,” he says. “Those methods are subsidies and cheap housing. Our goal is to achieve affordability through innovation, not by just making a cheaper product, but by using slices of land and time that most developers aren’t interested in.

“There are hundreds of small, irregular, pieces of land in our urban cores. There are also ways to subsidise rents through multi-use of space that is not possible without Kasita tech.”

Efficiency and choice

Ian Killick, of the UK-based architectural firm ShedKM, agrees that the resurgence of prefab is linked to the housing supply crisis – alongside factors such as the need for speed and a higher demand for customisation. His Town House project has been described as a ‘new concept for mass housing’, in that it consists of modular homes with flexible internal designs.

“Town House is basically about customer choice,” he says. “Not just the kitchen design or the colour of the front door, but properly customisable layouts and arrangements that can be tailored to purchasers and built to order. Prefabrication was a way of achieving this within a manageable timescale.”

To date, the project includes 43 houses in Manchester, with others due to be erected in sites across the UK. The appeal from the customer side is obvious: while the houses look the same on the outside, residents can choose between open-plan and room-based layouts, giving them a freedom of choice largely missing from city centres. From a construction standpoint, there is scope to save time and money.

“Manufacturing the houses in a factory allows the ground works and landscaping to be done concurrently,” says Killick. “All the hardscape and services on our Town House schemes are completed before the houses arrive, shortening handover times. The traditional building site is like a pop-up event, only there for the duration: there is an inherent efficiency in that.”

Homes as products

Clearly, projects of this kind would be impossible without recent technological advances. Techniques such as additive manufacturing and digital modeling tools have opened new possibilities for planners and architects, and robotics has started to enable mass construction at speed.

Just as important, however, is a conceptual shift, in which homes are envisioned less as buildings, but more as products or even services.

“In a sense, architects need to think like industrial designers and software architects, and those designers and software architects need to start understanding the mind of the architect. Rethinking homes as a product allows for iteration, branding, mass manufacturability, and [through] technology integration we can pull inefficiencies out of the system,” says Wilson.

Skilpod, a Belgian prefab construction company, goes one step further: while specialising in cross laminated timber houses, it sees itself predominantly as a product development company. The founders believe that housing will ultimately be branded in the same way as food and clothing.

“If you make a product and you want to scale up on an international level, you need a recognisable design that people love and production in a controlled environment,” says Skilpod’s Jan Vrijs. “You have to make clear choices and keep focus so in the end you can continuously optimise your product and offer your customers the best quality for the best price.”

A disruptive approach

It’s certainly a disruptive way to look at construction, and perhaps for the time being, it will remain a minority view. Despite the buzz surrounding prefab, the vast majority of buildings are still constructed on site, with activity limited by a lack of manufacturing capabilities. If demand is sustained, however, then supply will surely start to rise.

Killick believes that, while prefab is not the only way to build, it is certainly an interesting area for architects to explore. He feels that architects can help stoke demand by positioning prefab as something exciting in its own right.

“Unfortunately, many manufacturers seem to think their products need to imitate traditional forms of construction, almost to disguise the prefabrication aspect. Architects have a role to play in changing this attitude and encouraging a more honest approach,” he says.

Wilson adds that, while there will always be a need for traditional construction, what we are likely to see is a shift in how society relates to the home. This will prompt architects to look more closely at prefabrication.

“In the future, home will not be a fixed set of sticks and bricks in a certain place for 30 years – It will be a home that is with you, wherever you are. We wanted and were promised modular before today. Now, we need modular – that’s the difference,” he explains.