3D printing, or additive manufacturing, has become big news in manufacturing circles during the last few years, despite being a concept which has been around for several decades now. Originally conceived as a means of automating the prototyping process by creating a computer model of an object that can then be automatically built, layer-by-layer, by curing UV-sensitive resin with ultraviolet light, additive manufacturing has since progressed beyond its original purpose of creating prototypes.

Today, the sophistication of 3D printing processes is such that it is seen by many as a potential method of actual commercial manufacturing, or even a way of allowing end users to ‘print’ their own products.

As such, the main push for developers of the technology has been to look at the small scale, making the process more accurate and intricate, in search of the 3D printing Holy Grail: low-cost, end-use industrial and consumer products.

Loughborough University’s Freeform Construction project

While most labour on the micro scale to improve detail and precision, others are working to scale the concept up to a level that would be applicable to the design and construction industries. A team at Loughborough University in the UK, led by Dr Richard Buswell and Dr Sungwoo Lim of Loughborough’s School of Civil and Building Engineering, has made particularly impressive strides with its Freeform Construction project.

The team is applying additive manufacturing processes to create a concrete printing process that could automate the manufacturing of even the most complex architectural components. “Construction is using more and more solid geometry and computer modelling, and obviously CNC manufacturing is commonplace,” says Buswell, commenting on the decision to try and bring additive manufacturing to the construction industry. “It seemed a logical step to explore whether these layer-based processes had some value.”

But in a modern industry with a wide range of construction materials available, why concrete? Buswell notes that although the process could be applied to plenty of other materials, the team’s choice of this traditional base was the result of a mix of pragmatic decisions and in-house expertise.

“It’s a pretty well known material in the construction industry,” says Buswell. “So having conversations with what is a very conservative industry, it gives us a common language. I think that helps us get across that radical barrier. Plus, it means that we can adopt all sorts of standard testing on it, so people have some confidence with the sort of material properties we’re able to achieve with the concrete we’re using.”

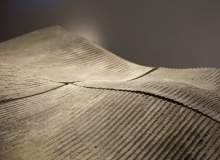

The project now has its proof of concept, a massive, one ton reinforced concrete panel that undulates with the kind of organic flow which would be costly and time-consuming to achieve using standard concrete moulding methods. The team’s work is being done in partnership with major design and construction firms, such as Buro Happold and Foster & Partners, who are providing the industry-specific feedback necessary to make this technology a reality for a market which prizes efficiency and value for money above all else.

Concrete printing: how does it work?

The team’s end goal is to bring 3D printing to the construction site, giving contractors and their suppliers the flexibility to print construction-grade concrete components to precise digital specifications, meaning large, complex curved panels can be produced without extra cost or labour. The process also means new components can be quickly created if designs or construction plans change. Theoretically, as long as a digital CAD model can be made, the sky is the limit.

As Buswell explains, the technological framework of the project is essentially the same additive manufacturing process that has been in place for years, but brought up to an unprecedented scale.

“The scale is key,” he says. “Fundamentally and conceptually, it’s really no different from other additive manufacturing processes, but obviously in a practical sense you’re dealing with different materials, different properties, and the weights and the physical sizes of the parts are quite high.”

The team originally developed the process using a large XY gantry, but Buswell thinks that robotic arms will ultimately be better suited to delivering the large-scale additive manufacturing capability the process requires, while taking up less space and being easier to manoeuvre.

“We’re currently commissioning a seven-axis robot to use the process with, and robots are relatively inexpensive and used more readily,” he says. “We’re seeing that the way forward is a process where you could just recommission robot arms with the right equipment, and use those to be able to manufacture panels with. You could potentially get a second-hand robotic arm for 50 grand, recommission it and you could be making freeform panels with it.”

In terms of the practical implementation of the technology for construction projects, the options are still open. Although it would theoretically be possible to set up an additive manufacturing plant on a construction site, the Loughborough team believes it would be better suited to a controlled factory environment because of the unpredictable environmental conditions on an average construction site. On large high-end projects, however, Buswell notes that it would be possible to establish a temporary on-site plant to eliminate logistics and transport costs.

Applications and advantages to concrete printing

Given the radical nature of the technology and the conservativism of the construction industry, the team’s concrete printing process will likely have high-end, complex construction projects as its market entry point.

For ambitious designs that emphasise flowing curves and other complex shapes, additive manufacturing offers the ability to achieve that complexity and variety – the personal touch – at the same cost as any other shape.

“At first, it’ll probably be used on the very high-end buildings with clients who can afford to be extravagant with new technology,” says Buswell. “The advantage is that you can produce virtually any part you want, so there’s no reason why you can’t produce boring flat parts with it, but there’s not really any advantage over existing processes. So I think it’s where you want curvature, where you want something a bit special. But then it might make the double-curved building much more affordable.”

Related project

Seattle Jelly Bean Concept, Washington, United States of America

The Seattle Jelly Bean is an innovative design concept participating in the Urban Intervention competition at the Seattle Center in Washington, US.

The team’s partnership with Buro Happold and Foster & Partners has provided insight into the technology’s implications for the design process. As this new frontier of construction and design opens up, there will inevitably be an awkward transitional period as designers get used to a new system and address the challenges of integrating additive manufacturing into a practical construction project.

But Buswell is confident that the process will offer more options to design teams. “From the overall architectural form point of view, maybe you’re [more able] to do what you want to do, rather than going through that value process where you have to make surfaces faceted and you have to start changing the design to get the curvature.”

Looking to the future, Buswell says it’s possible that 3D printing could eventually the main manufacturing point for entire projects, using a range of different materials. It’s certainly not unreasonable to imagine that, in decades to come, the layers of additive manufacturing could be building skyscrapers from base to tip.

But while it’s exciting to speculate about the far-flung possibilities of this technology, the job at hand is to take the first step by persuading architects and construction firms that there’s a financial and logistical reason to invest in concrete printing methods. “With everything, it’s always down to value and cost,” says Buswell. “And the cost of any system will come down with use. If it proves to be the right way, the construction industry will accept it as such.”