In 2005, the Shanghai Industrial Investment Corporation (SIIC) hired the global design, engineering and business consultancy firm Arup to design and plan a city. The goal was to make it as close to carbon neutral and zero waste as possible. When Dongtan Eco-City is built on an island near Shanghai, this development could bring increased sustainability to a region rife with crowding and pollution.

Arup claims that, compared with typical developments, the city will have an ecological footprint that is 60% smaller, will require 66% less energy, will produce 40% of its energy from bio-energy and emit almost no carbon dioxide.

Dongtan design and construction

The city is planned for Chongming Island, situated in the mouth of the Yangtze River, where it empties into the East China Sea. Across the river lies Shanghai, the largest of five cities in the Yangtze River Delta area. Nearly 90 million people live in the region, one of the most densely populated in the world.

Chongming, the third-largest island in China (at 1,200km² or 120,000ha), has been an agricultural area and is much less crowded than the rest of the region. Chongming’s population is expected to surge with the 2009 completion of a bridge and tunnel to Shanghai.

At present, a ferry is the only connection. In addition, the Three Gorges Dam project has displaced many people, some of whom will likely move to Chongming.

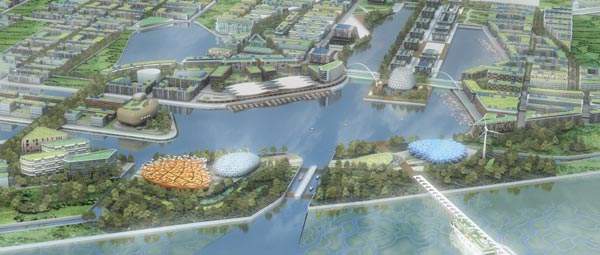

Dongtan (which means ‘East Beach’) will go on the island’s southeastern tip, covering 86km² (8,600ha). When construction ends in 30 or 40 years, 500,000 people will likely live in Dongtan’s three villages. Although some may commute to Shanghai, the intention is to attract companies to Dongtan so that most residents can work on the island.

Arup has produced a master plan and sustainability guidelines. Dongtan now has ten wind turbines but no buildings. Construction was slated to start in 2006 but has yet to begin. Originally, the eco-city was supposed to be able to accommodate 50,000 people in time for the Expo 2010 in Shanghai, but Arup says construction cannot start until Chinese officials issue the necessary permissions. Some sources say that the land use term has expired.

Environmental effects and energy supply

Delicate wetlands on Chongming, the world’s largest alluvial island, are home to migrating water birds and are of global importance. Arup maintains that it will protect and enhance the wetlands adjacent to Dongtan in several ways: by returning agricultural land to a wetland state, by creating a wide ‘buffer zone’ (3.5km across at its narrowest point) between the city and mudflats, by building on less than 40% of the Dongtan site and by preventing pollutants (light, sound, emissions and water discharges) from reaching the wetlands.

During construction, Arup plans to source labour and materials locally whenever possible. This should reduce transport and embodied energy costs.

After construction, the buildings themselves should place less of a burden on the environment than is typical. Arup claims that its well-insulated buildings, outfitted with energy-efficient equipment, will use 66% less energy than buildings usually do and will emit 350,000 fewer tonnes of CO2 annually. The buildings will be naturally ventilated, thereby requiring less energy. Green roofs will improve insulation and water filtration.

Planners want Dongtan to eventually become a zero-waste city. Until that happens, the city will collect 100% of waste (including sewage), using 90% of the waste as a source of energy, irrigation and composting. Some of the processed waste will serve as fertiliser in the city’s organic farms. Dongtan will not have a landfill.

Dongtan will produce all of its own electricity and heat, says Arup. Buildings and vehicles will run on renewable energy sourced from the wind (via a wind farm and micro wind turbines on buildings) and sun (via photovoltaic cells). A combined heat and power plant will run on rice husks discarded by local rice mills. Treating municipal solid waste and sewage will generate biogas, another energy source.

Dongtan transportation

With three villages that meet at a commercial centre, Dongtan will feature a compact layout that will minimise the need for motorised journeys within the city. All housing should be within a seven-minute walk of public transport. Businesses, schools, hospitals and the like should also be easily accessible. Arup claims that such accessibility will reduce travel distances, thereby lowering CO2 emissions by 400,000t annually.

Visitors will need to park outside the city. Transportation options within the city will include cycling, walking, hydrogen fuel-cell buses and solar-powered water taxis. The boats will use a network of canals and lakes.

In Dongtan, all vehicles will run on batteries or hydrogen fuel cells. These energy-efficient vehicles will emit practically no greenhouse gases.

Despite all these plans, the city is not expected to achieve perfect sustainability.