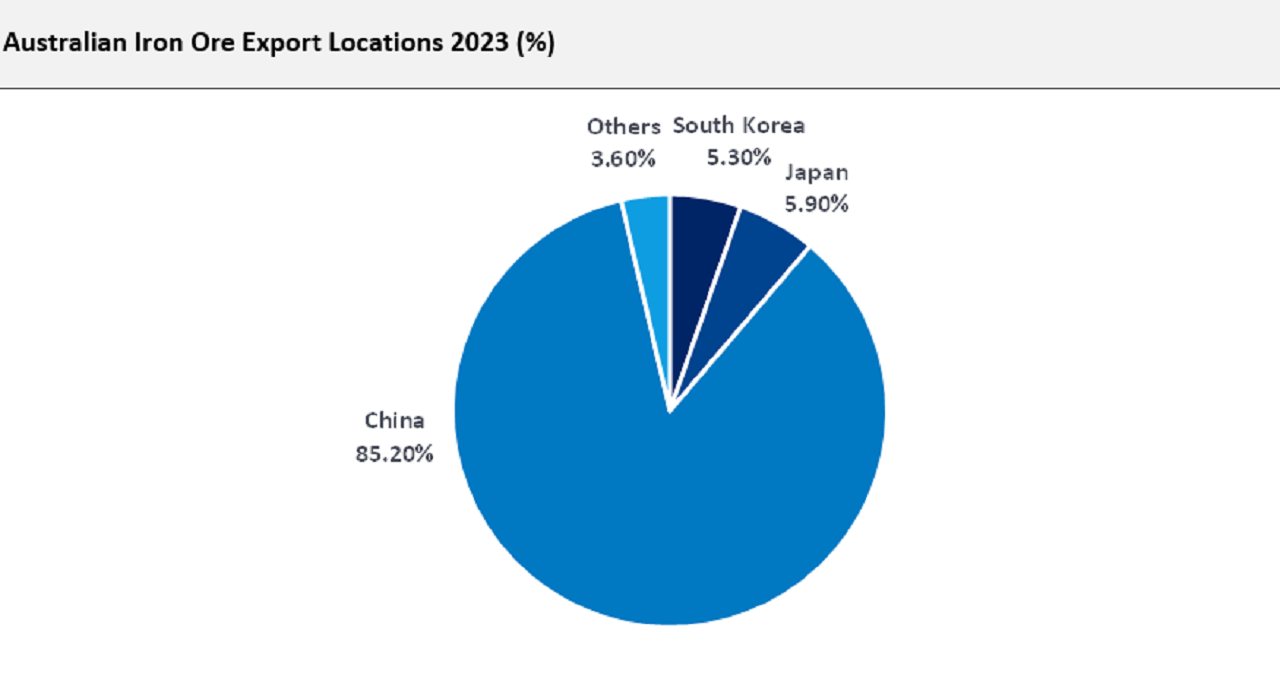

Before the proposed announcement of US tariffs on metal imports, Australia was not subject to direct tariff measures by the US. However, following the Trump administration imposing a 10% tariff on all Chinese imports, demand for Chinese products is expected to decline over the next period. Given that China is Australia’s largest trading partner, Chinese tariffs would therefore indirectly cause knock-on effects for the Australian economy, reducing demand. For example, tariffs in China would likely cause steel demand to decline, impacting the Australian iron ore industry, which exported 85.2% of its iron ore to China in 2023. Furthermore, if tariffs are inflationary in the US, this may cause the Federal Reserve to revise its monetary easing schedule. Consequently, this may restrict the Reserve Bank of Australia’s capacity to also enact interest rate cuts moving forward due to a potential divergence in monetary policy between the two nations. Tariffs may also apply downward pressure on the price of the Australian dollar, making imports more expensive, which could be inflationary, while Australian exports would be cheaper for foreign buyers. Additionally, due to the intra-dependence of trade flows, rising supply chain costs could also lead to rising import prices in Australia, further contributing to rising inflation. Generally, higher interest rates and rising production costs would likely lower project viability for contractors, directly reducing Australian contractors’ construction capacity and potentially causing projects to be cancelled or watered down. Even if Australia is not directly affected by US tariffs, a broad US levy on construction materials could lead to overseas producers looking to alternative markets to sell cheap steel and aluminium. As a result, this could undercut the Australian domestic manufacturing sector. On the other hand, the US’ escalating trade war with China could benefit some Australian metal producers. China currently possesses a comparative advantage in critical rare minerals such as tungsten, tellurium, and molybdenum, which are commonly used in goods such as solar panels and smartphones. Retaliatory import tariffs by China may cause some US manufacturers to turn to other mineral-rich countries such as Australia or Canada, benefitting local suppliers.

Trump’s proposed announcement of a blanket 25% tariff on all steel and aluminium imports into the US will severely impact Australian mining companies, as well as manufacturers and contractors in both the US and Australian construction industries. According to the UN’s COMTRADE database, the US imported approximately A$638m ($400m) worth of Australian steel in 2024 while the US is also Australia’s third largest export market for aluminium, with only South Korea and Japan importing more. A 25% tariff would increase the price of Australian steel and aluminium imports for US buyers, leading to a reduction in demand for the commodities. However, the reduction in demand for Australian products will depend on the extent to which US buyers will be able to substitute domestic steel products for Australian imports. Most likely, this will create excess demand in the US, leading to rising prices for US producers and consumers, who may still need to import Australian metals to meet demand. Following the announcement of Trump’s proposed policy on 10 February 2025, A$15bn was wiped off the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), with the benchmark ASX200 tumbling 0.5% in the first hour of trading.

However, when similar tariffs on metals were imposed during Trump’s first presidency, Australia, alongside Canada, Mexico, the EU and the UK were exempted from the policy. Therefore, a potential watering down or removal of metal tariffs in Australia is still a possibility given the importance of the commodities for US companies. Moreover, on 20 January 2025, Donald Trump directed the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to identify prospective countries where the US could negotiate bilateral or sectoral deals with the aim of securing market access for US exporters. These deals are unlikely to be free trade agreements but still aim to enable market access for US companies to directly compete with domestic markets in foreign countries, potentially creating a platform for negotiation. In addition, Trump’s USTR memo also ordered a review of other countries’ unfair trade practices. Previously, a USTR report into foreign trade barriers identified Australia’s restrictions on beef, pork, cooked turkey meat, apples, and pears as high-priority trade barriers. In addition, there were also concerns regarding aspects of Australian patent protection for pharmaceuticals and content requirements for streaming platforms. Despite this, even if the USTR does choose to target Australia specifically, it is unlikely to do so ahead of the many countries where barriers to US exports are more extensive.