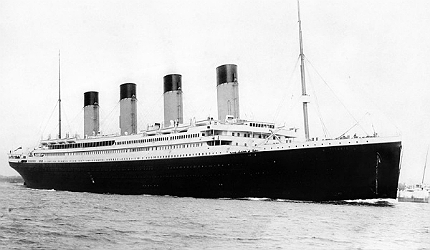

It’s the century year of the Titanic’s maiden voyage and to commemorate the glory and tragedy of the doomed ship, the world’s largest exhibition has opened in the city where she was built.

Titanic Belfast has been designed to tell a story not just of a ship that sunk, but of a time and a place where shipbuilding was rife and the economy was healthy.

The three-dimensional space charts the growth of the Harland and Wolff shipyard, the life and times of people who crafted the Titanic and the passengers who sailed on her.

James Alexander, CEO of exhibition design consultancy Event Communications, tells designbuild-network about how his team recaptured Edwardian Belfast and the story of the world’s most famous passenger liner, and how they created an environment which resonates with diverse audiences around the globe.

What inspired you to become involved in the Titanic Belfast project?

Related project

Titanic Belfast Exhibition for Titanic Centenary, Belfast, UK

Titanic Belfast is an architectural masterpiece opened on 31 March 2012, days before the centenary of the Titanic ship’s maiden voyage in April.

James Alexander: I think the fact that it’s Titanic makes it pretty special.

I think doing something on the Titanic in Belfast, which is of course the place where the Titanic was built, is also pretty special.

There are other Titanic exhibitions which have opened recently – one in Southampton for example – but there is something about developing a Titanic story in its home town.

It was always going to be very appealing. One hundred years ago Belfast was very important city. In fact, it was one of the most important cities in the Commonwealth and was comparable to Liverpool and Glasgow in terms of its shipbuilding.

How did this particular project differ from your previous exhibition designs?

![]()

Event Communications has recreated interior spaces from the Titanic using modern materials. Image courtesy of Titanic Belfast.

JA: It didn’t differ hugely. Our job as exhibition designers is to deliver stories and narrative – it’s what we do for a living, so in this case it was about the story of Belfast and the Titanic.

How have you created a space which tells the story of the Titanic while creating a visual representation of the liner?

JA: It’s called the Titanic exhibition, but actually we are telling the story of Belfast too. So we were wrapping a wider story around the ship, which gives it a broader basis of interest.

There are nine galleries and we have created in each of those galleries a narrative which flows chronologically, so when you walk into the first gallery you enter Edwardian Belfast and the city streets and you go on journey through those streets, which illustrate what it was like to be in Belfast at that time.

Then you go through the drawing offices, the shipyard, the launch, the fit-out, and then after the Titanic is sunk we bring the chronology forward to the issue of myths and legends and the discovery of the ship in the 1980s.

What materials did you use to emulate the original interior design?

JA: All sorts. One of the things about this project is that 100 years isn’t a huge amount of time ago and the records for the Titanic and its sister ships, the Olympic and the Britannic, all exist.

So we have recreated, in a number of ways, the interior spaces which include three scale mock-ups of first class, second class and third class cabins, and we had enough detail to be able to do that very precisely.

We’ve also created what we call a 3D cave, which people can walk into and take a journey through the Titanic, from the boiler rooms up to the captain’s bridge. With all these things we used modern technologies and modern materials, but they are based on the reality of the drawings from the first decade of the 20th century.

We don’t have a lot of collections of objects like in a museum, so we are having to create immersive environments using moving and still footage and we are projecting that at large scale to give a sense of presence. We’ve also got a ride, which takes people through the shipyard as the Titanic is being built at different stages, such as the laying of the keel through to the plating and riveting process.

Did you feel under pressure when designing this exhibition, knowing the tragedy behind the Titanic and how many lives it effected?

JA: I don’t think so. Clearly it was a tragedy, but it’s a well understood tragedy and I think that a lot of what we deal with can have tragic components. We worked on the Imperial War Museum, for example.

I think what we were very conscious of is to ensure that when we tell the story people are engaged with it emotionally, on all kinds of different levels. This isn’t a simple case of Belfast building a ship and the ship sinking, it’s a story about the people that built the ship. It’s Belfast’s very personal story and if you go to the Titanic exhibition, what you’ll see is a huge effort made to tease out the personal and human stories and that’s very, very important, because people relate to people.

We were certainly conscious of getting the facts right, but I wouldn’t say we were worried because most of our clients are museums and when you are working with museums, you can’t get it wrong.

How did you decide which elements of the ship to incorporate into your design and which individual stories to tell?

JA: What we did at the beginning of the process was write a narrative for the exhibition and as this developed we made appropriate judgements about what part of the ship, or the process, that we wanted to highlight.

So in the ride, where we illustrate the construction process, we have created part of the Arrol Gantry, which is the scaffolding in which the titanic sat while it was being constructed.

But, when it came to the fit-out of components, that’s where we have reconstructions of the cabins, for example, so it depended on how the narrative flowed.

How long did it take you to research the Titanic to ensure the content of the exhibition was rooted on fact?

JA: We began in 2004, so we’ve been at it a while and of course that intensified through the design process. In Belfast there is a Titanic society that involves family members of the passengers and we spoke to these people, but also we set up an ‘experts group’ to help us ensure that the stories that we did have were factually correct.

What were the main challenges you faced during the project?

Titanic Belfast has been designed to tell a story not just of a ship that sunk, but of a time and a place where shipbuilding was rife and the economy was healthy.

JA: The time scale was the main challenge. Although we had been working on the project since 2004, it didn’t get the green light until 2010, so once we finally got the go-ahead there was quite a lot to do. It took that long because we began by doing various feasibility studies, plus the total project cost is £97m and raising that kind of money took a while.